Date: May 2012. Location: Williams Prairie

| Classification Hierarchy | |

| Kingdom | Plantae |

| Subkingdom | Tracheophyta |

| Superdivision | Spermatophyta |

| Division | Magnoliophyta |

| Class | Magnoliopsida |

| Subclass | Magnoliidae |

| Order | Ranunculales |

| Family | Ranunculaceae |

| Genus | Ranunculus |

| Species | Ranunculus hispidus |

Date: May 2012. Location: Williams Prairie

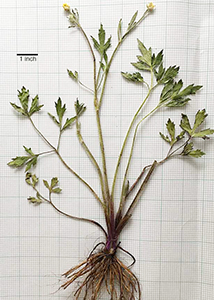

Scientific Name: Ranunculus hispidus—three varieties: var. caricetorum (among sedges), hispidus (hairy), and nitidus (shiny).

Common Name: bristly buttercup

Origin: Native

Notes: The plants in the photos below grow in a wetland prairie along with numerous species of sedges. Until recently the plants have been called Ranunculus septentrionalis. However, a taxonomic revision has made R. septentrionalis a synonym for R. hispidus variety nitidus—which is one of the two varieties of R. hispidus reported in Iowa. The other variety is caricetorum. It's name indicates an association with sedges. The photos below exhibit properties that are characteristic of both varieties. There is more about this in the comments section below the photos.

Additional references: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11.

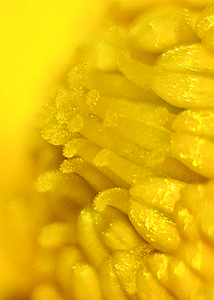

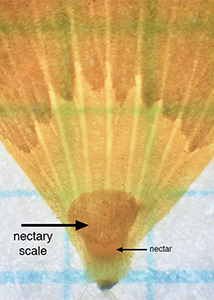

1. Flowers in this population were normally five petaled but occasionally the flowers produced were six or seven petaled.

2. These plants grew in standing water or saturated soils.

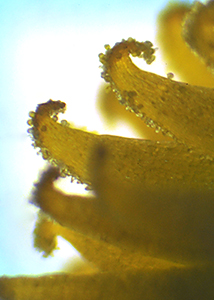

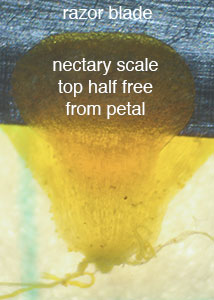

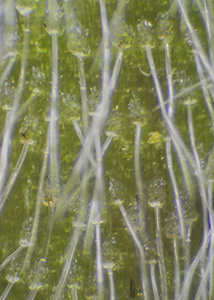

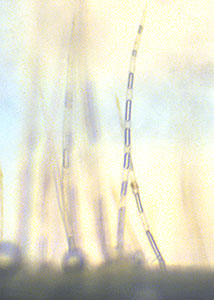

4. When the water column was broken by cutting the stem for sectioning, cavitation bubbles appeared in some of the stem hair cells. Undamaged hair cells seem to be filled with water. Perhaps they have a role in the plants regulation of water movement.

Comments: Early in its description of the genus Ranunculus the FNA says, "The genus is badly in need of biosystematic work." The following examination of Ranunculus hispidus seems to bear that out. Two rather heroic studies have provided much of what is known about Ranunculus today. The first was A treatise on the North American Ranunculi (1948) by L.D. Benson and the second was A Taxonomic Study of the Ranunculus Hispidus Michaux Complex in the Western Hemisphere, Volume 77 (1980) by Thomas Duncan (which can be seen on Google Books).

The 1980 Thomas Duncan study provides a short history of taxonomic problems with Ranunculus and also, after examining many populations of Ranunculus—species and varieties—he suggested characteristics that would most reliably identify these taxa. Duncan's discussion (page 40) observes that in the vegetative state the three varieties of R. hispidus are hard to distinguish except that variety hispidus is an upland plant and the other two varieties (nitidus and caricetorum) are found in lowland or swampy habitats. Duncan recalls a statement by Benson (1948) that "the only features consistant within this group are the achene margin and the plant habit" (i.e. whether the stems are erect, repent, or stoloniferous). This plus the most recent characterization of the three varieties by the FNA can be summarized as follows:

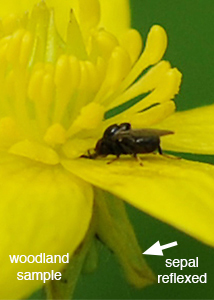

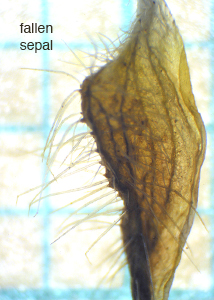

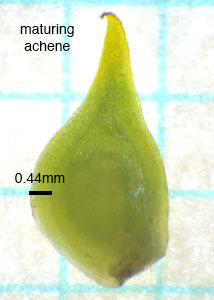

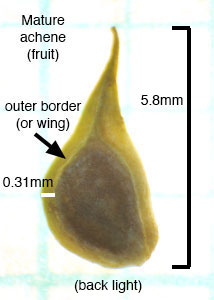

1. R. hispidus var. hispidus has sepals that may be either spreading or reflexed and its achene margins are less than 0.2mm wide. It tends to be an upland plant with upright stems that are never stoloniferous. This variety has not been reported in Iowa. The other two varieties are usually lowland plants (marshes and woodlands) and at the time of fruit maturity, have decumbent stems that sometimes root at the nodes. Both of these have been reported in Iowa (USDA). The more abundant of the two, R. hispidus var. nitidus , is probably better known locally by its synonym R. septentrionalis.

The FNA separates the two lowland varieties on the basis of two features—how the sepals are held and the width of the borders on an achene.

2. R. hispidus var. caricetorum has sepals that may be either spreading or reflexed and its achene margins are less than 0.2mm wide.

3. R. hispidus var. nitidus always has reflexed sepals and the achene margins are between 0.4mm and 1.2mm wide.

Discussion: Now, let's consider the plants in the photos above. They are all from a population (100+ plants) growing in a wet area called a sedge meadow, because of the abundant sedges. There is usually standing water and rivulets of water running through the area in the spring when the plants are in bud. Some degree of drying takes place during the summer, generally after the fruit (achenes) have dropped. Several years ago the plants had been identified as Ranunculus septentrionalis—which is now considered a synonym for R. hispidus var. nitidus.

The chromosome number for the plants in the photos is presently unknown. But, while they are not much use for field identification, chromosome numbers provide another distinction between the three varieties of R. hispidus. Varieties nitidus and hispidus are tetraploid (n=16); variety caricetorum is octoploid (n=32) [Table 6 on page 32, see the Duncan link above]. Keep in mind that normally two organisms with different chromosome numbers (such as var. nitidus and var. caricetorum) can not form viable hybrids. So, while the plants described here have features from both varieties, we shouldn't expect them to be hybrids of the two varieties.

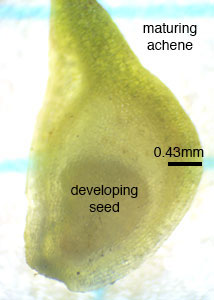

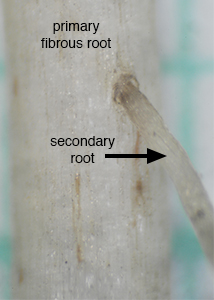

These plants key out nicely to Ranunculus hispidus. The challenge is to determine which of the three varieties they represent. When the young plants first flower, many were crowded by neighboring sedges and the Ranunculus stems were held upright. Plants with upright stems could have been var. hispidus. But, by the time that the achenes had matured there were decumbent stems (stolons) growing through the wet and dense vegetation around the base of the plant and some were rooting at the nodes. This growth habit and the lowland habitat indicates that the plants are not var. hispidus.

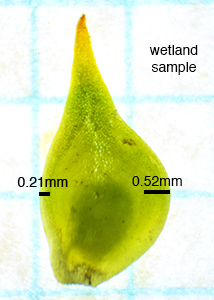

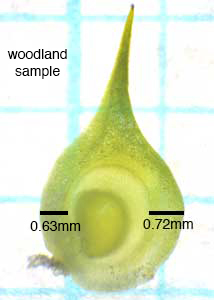

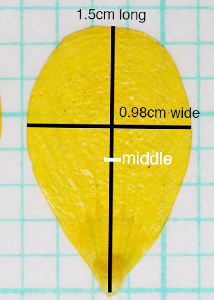

Since these plants were growing among sedges and the latinized word caricetorum means growing with sedges, perhaps these could be examples of variety caricetorum. But the achene borders were too broad (more than 0.3mm). Because there was variation in the size and shape of the borders; I spent some time collecting achenes and measuring borders. On one occasion I checked all of the achene borders in one head and on another occasion I collected and measured achenes as the plants developed from buds to mature fruit—in case the border size changed during development. There were some variations in border sizes and a few obvious abberation that I ignored. The border size appears to be consistant enough to distinguish between achenes with broad border widths (greater than 0.3mm) and those with narrow border widths (less than 0.2mm) provided all measurements are made at the same part of the border (I used the midpoint of the back (abaxial) side of the achene). The border width on a single achene can vary more than 0.1mm depending on where the measurement is made (see photos above). Since I did not find any narrow bordered achenes in this wetland population of plants, I can say that they are not var. caricetorum. The final option, variety nitidus, seems a good choice since its synonym R. septentrionalis was originally assigned to these plants. However, the FNA key allows var. nitidus to have only reflexed sepals and these plants all have spreading sepals. So according to the key, they are not var. nitidus.

Hence, the dilemma; the plants key nicely to the species (R. hispidus) but do not match any of the varieties of which the species is believed to be composed. Perhaps the problem is with the description of the sepals. The FNA key allows the other two varieties to include plants with either spreading or reflexed sepals. If the same could be done for var. nitidus the plants in the photos would easily fit the circumscription for var. nitidus. In which case, the key to the varieties would have no need to mention the position of the sepals for any of the varieties.

Addendum: The photos below compare the same wetland plants (top row) with plants from a woodland population (bottom row) which had also been formerly identified as R. septentrionalis. The woodland plants grew in moist and wet soils along a creek bed but not in standing water. While they bloomed at the same time as the wetland plants and they demonstrated the reflexed sepals expected in R. hispidus var. nitidus, their stems are thiner, stronger, and less hairy than those of the wetland plants. Perhaps one day a genomics study will add more clarity to the relationship between Ranunculus taxa.